Mapping the EU AI Landscape (Part 1): Coordinated Plan on AI

BlogPostOct 13, 2024

DISCALIMER:** The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely my own and do not reflect those of my employer, or any of its affiliates.

Intro

In the previous post we figured out that the Horizon Europe project contains some redundancies in AI-related project. My next step was to figure out a fix to this problem, but in order to do so, I had to dig deep into how the EU handles AI projects and agendas. I started off easy, asking ChatGPT to provide a list of EU policies,organizations and anything else related to AI. Of course, the first suggestion was the EU AI Act which I’m now familiar with, and this just made me feel a bit cocky, thinking I was already an expert. Well, the second suggestion was the Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence (PlanAI). It’s just a plan, how complicated can it be? Well, let’s just say the rabbit hole was deeper than expected.

So, join me in this journey of dead links and never-ending references. In this post (probably the first of a series), we’ll dissect the PlanAI and see how many projects are connected to it. If you prefer a visual approach, I made this nice graph where all these initiatives are connected and can be interacted with. The graph will be continuously updated, so don’t worry if some info is missing right now.

Let’s begin.

Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence

The PlanAI was first published in 2018 and then reviewed in 20211, when the EU (and the world) realized the potential impact of AI. The changes between the two versions mainly focus on:

- Planning: The 2021 version emphasizes human-centric, sustainable and secure AI. It also aims to achieve EU digital sovereignty.

- Funding: This is the most significant difference. The original plan was to invest at least €20 billion by 2020 using the Horizon 2020 and Horizon EU. The new plan increased the target quite a bit, now aiming for €145 billion by 2023 through Horizon EU, the Digital Europe Programme and the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

For everything else, the new PlanAI is based on four policies reflecting key objectives in AI.

1. Enabling Conditions for AI’s Development and Uptake

Let’s abbreviate it to EnablingAI. Here, the aim is to actually have the resources necessary to make AI a reality in EU. This translates in launching two new initiatives: AI Factories and GenAI4EU.

AI Factories

Announced in January 2024, the AI Factories will come to life in 2025 and are currently just an amendment to the The European High Performance Computing Joint Undertaking (EuroHPC JU). So, for now, we only have a vague description of what a factory will look like. Specifically, it will include a mix of hardware (supercomputers and data centers), “human capital” (I guess they mean experts from academia and research institutes), and startups/SMEs.

But how? Well, the commission and member states will invest an additional €2.1 billion to acquire more computing power. On top of that, the commission will provide financial support for startups (at least €100 million) with a cap of €1 billion coming from InvestEU.

GenAI4EU

Honestly, I couldn’t find much on what these are supposed to be. The description states it “aims to support the development of novel use cases and emerging applications in Europe’s 14 industrial ecosystems, as well as the public sector. Application areas include robotics, health, biotech, manufacturing, mobility, climate and virtual worlds.” What I could find is that the commission is planning to use the Horizon Europe and the Digital Europe programmes to fund projects that are connected to industry application of GenAI (in the above field) for a total of €500 million2. Also these initiatives will cooperate with the AI Factories and the Common European Data Spaces. I guess the latter will provide compute/experts and the former data. Finally, the EU AI Office together with the European Transition Pathways Platform will, will monitor GenAI4EU’s progress.

2. Thriving From the Lab to the Market

While point 1 focused on the material necessities to build AI (mainly computing resources and experts), the aiLabMarket focuses on fostering Public-Private Partnerships (PPP). Specifically, the Commission will provide a €1 billion per year in investments in AI through our friends: Horizon Europe and the Digital Europe. Another €20 billion will be provided by member states and the private sector. Finally, the whole initiative can utilize the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) funds3, which amount to €134 billion.

Of course, to do so, you need to intervene in various aspects:

- The actual coordination between experts (academia) and private sector: Enter The AI, Data and Robotic Association (ADRA) (more about it later).

- Support for smaller players: If you’re a small player with a big idea, you can hop on the (https://www.ai4europe.eu/) and check what available resources (algorithms, data, and computing power) you can use to achieve your goals!

- Regional-level support: The (https://european-digital-innovation-hubs.ec.europa.eu/home) can help at a regional level.

- How do you coordinate between experts and private sector if you have no experts? You need a network of (academic) organizations that foster AI research of course. That’s why the European Networks of Excellence in AI (NoEs) exits.

- Ok, you have the experts and the private partners. They come up with a nice idea and implement it. Will it be in line with the never-ending, always-changing EU regulations? Why don’t you try your idea out in the newly created testing and experimentation facilities (TEFs)!

In the next parts, we will explore each of these points in detail.

AI, Data and Robotics Association (ADRA)

As mentioned before, ADRA is an association with the aim of promoting PPP by accessing €2.6 billion euros from the Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe funds (with additional contributions by private partners). It’s called association right? So who are the members? Well, the initial ones were:

- Big Data Value Association (BDVA)

- Confederation of Laboratories for Artificial Intelligence Research in Europe (CAIRNE)4

- European Laboratory for Learning and Intelligent Systems (ELLIS)

- European Association for Artificial Intelligence (EurAI)

- European Robotic Forum (euRobotics)

Hopefully, we’ll have time and energies to figure out where these organizations come from later. As now (06/10/2024) there are a total of 140 Members: 88 Research, 47 industry, 4 associate and 1 strategic (Sweden AI). Not bad, considering the project is 3 years old (created in May 2021) and they managed to get major players on board (e.g. BMW, Decathlon, Bosch…).

Goals

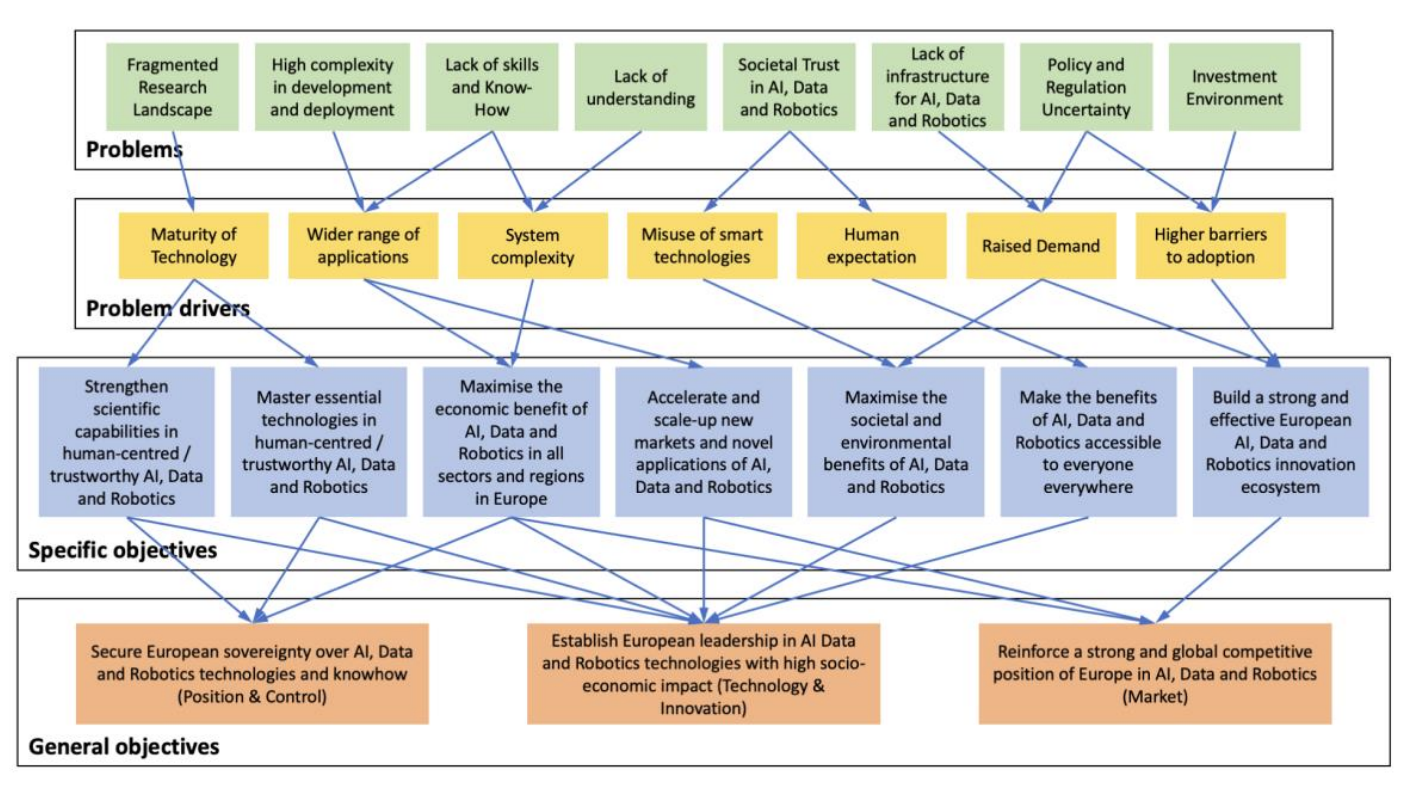

Going back the ADRA’s goals, as stated in the Partnership Proposal they have three general objectives divided in seven specific ones (see Figure —ADRA, please don’t sue me for using your picture).

Apart from the usual suspects (securing European sovereignty), we can see a specific aim to promote the creation of innovative5 initiatives6 aimed at maximizing societal7 and economical8 benefits. To me, it seems that ADRA has the most challenging objective: balancing EU values for societal benefits (avoiding risky use cases), with regulatory/market fragmentation and uncertainty, and companies objectives. Good luck.

How?

ADRA’s proposal (Section 3) lists a number of activities in order to achieve its goals.

Basically, these activities can be divided into support for innovation (lighthouses, mission-based challenges, cascade actions, actions to stimulate uptake, and market/innovation enablers) or support for ecosystems (community building, business models/organizations, regulatory/standards and task forces).

Current status

Currently, ADRA released the fourth edition of theStrategic Research, Innovation, and Deployment Agenda (SRIDA) where they outline “the long-term vision for the development and deployment of trustworthy AI, Data, and Robotics technologies in Europe and provides key recommendations to guide future European work programs.”. I highly suggest reading it. ADRA also has a series of forums ongoing, the latest being last November (which I missed it!).

AI-on-demand platform (AIoD)

While ADRA actively works on connecting the public and private sectors, it cannot materially help all possible small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). For these SMEs, a federated approach is more suitable, meaning that they need to help themselves. How can they do that? How can you, with a great business idea, look around and see what others are offering (algorithms, data, compute, expertise), and use those resources to your advantage? Well, have you heard of the AI-on-demand platform?

Besides having a slow website, the platform hosts several services:

- Assets Catalogue, aka MyLibrary, where you can access AI models, datasets, and experiments. In the dataset section, it mainly features content from Hugging Face, while the models seem to come from Bonseyes (a marketplace for AI in cloud and edge) and OpenML (another platform for AI stuff). It also mentions “powered by AI4Eosc”, which stands for Artificial Intelligence for the European Open Science Cloud.

- Research Bundles give you a space on the AI on-demand platform to collect and publish the outputs of a small research project in a compact way. A research bundle gathers in one place all the assets (code, data, tutorials, examples, etc.) produced by your project and published on the AIoD platform. Of course, you can also include links to assets published elsewhere, like GitHub or Zenodo.

- An AI builder created in partnership with Eclispe and built at Fraunhofer IAIS (wink wink).

- The Research and Innovation AI Lab (RAIL), a beta version of what seems to be an educational-oriented platform to use AIoD assets.

Speaking of funding, the platform is supported by Horizon 2020, Horizon Europe, and the Digital Europe programme (focused on industry and public administration), but I couldn’t find any specific numbers.

European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs)

So, if you got this far, you now know that if you’re a big company, ADRA will carry your hand through the EU regulations9, and if you’re small but independent, you can explore what AIoD has to offer.

But what happens when mamma ADRA has no time for you and you don’t understand what AIoD is all about (I feel you)? In that case, you can turn to your nearest European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs). EDIHs are regional hubs that promote digitalization for both the public and private sectors. There are currently 150 working in AI, with their objectives defined on the website as: “EDIHs help all companies seeking to use AI technologies to become more competitive on business/production processes, products or services.” If we choose a random one from the catalog, we see that they mostly provide support (check the services). While 50% of their costs are funded by the EU and member states, the remaining portion must be covered by private contributions and regional funding. I like this approach because it forces EDIHs to be active at the regional level, hopefully solving smaller but very real problems.

The website presents several more initiatives, which I’ll briefly list here, and we can see if they come up again:

- Digital Transformation Accelerator (DTA): A project that aims to support the creation, development, and growth of the pan-European DIH network, and facilitate intra/inter-regional collaboration between EDIHs. It ended in March 2022

- Digital Maturity Assessment Tool (DMAT): Developed by the European Commission Joint Research Centre (JRC), it’s a framework to measure the digital maturity of EDIH customers across Europe10.

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): A reporting tool used by EDIH to report their progress to the commission.

Networks of Excellence Centres (NoEs)

Until now, we’ve covered initiatives dedicated to bringing innovations to life with the support of experts. But what happens if there are no experts to rely on?

This is where the Networks of Excellence Centres (NoEs) come into play. Attentive readers may notice that the link for NoEs actually redirects to the Vision4Ai website. Digging around, I found that the VISION project was allocated ~ €2 million from Horizon 2020, and it lasted from September 1st 2020 until this August (31st, 2024). Its main objective was to coordinate the NoEs, and it appears they have achieved this goal. At this point, it’s unclear who will take on the role of coordinating the NoEs, but it could also be the case that such coordination is no longer necessary, as the centres are already in contact with each other.

Speaking of centers, these are the current ones:

| Start Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | AI4media | ELISE11 | Humane-AI net | TAILOR | |

| 2022 | ELSA | euROBIN | |||

| 2023 | ELIAS | dAIedge | Enfield |

Note: All centres established in 2020 ended in August 2024.

NoEs reports to be strongly linked to ADRA and wants all the projects to communicate via the AIoD platform.

As mentioned before, the primary focus here is on academia: “fostering research excellence and creating a critical mass of European AI knowledge and talent.”

Testing and Experimentation Facilities (TEFs)

Finally, we’ve reached the last initiative in aiLabMarket, which is related to the last step in the line: testing. For this purpose, the Commission has invested €200 million to create four sector-specific Testing and Experimentation Facilities (TEFs) for AI., specifically for:

- Healthcare with TEF-Health

- Agri-food with AgrifoodTEF

- Manufacturing with AI Matters

- Smart Cities & Communities with Citcom.ai

But what exactly are these facilities, and how does testing work? Let’s take a closer look.

We’ll use Citcom as an example since it relates to a filed I’m somewhat familiar with (smart-cities). Based on their website, they offer several services, ranging from providing access to data to conduct tests in real-life situation (e.g., deploying systems in Belgium). All of these services have a Technology Rediness Level (TRL) threshold of 6 to 8, meaning that your system must to be at least be demonstrated in a relevant environment.

Overall, TEFs are not overly complex. They are places where you can bring your system to be tested in a near-final environment. The official EU page also mentions that, after the initial five-year funding, the TEFs are expected “to achieve long-term financial sustainability”, which likely means companies need to pay for these services. Since testing is necessary to deploy your system at the EU level, it could become mandatory for companies looking to bring their products to the European market. The real question is whether these additional testing costs will be passed on to end users.

3. Ensuring That AI Works for People

To recap (I need this more than you): EnablingAI focuses on supporting the creation of “physical” AI infrastructures (e.g., compute centers), while aiLabMarket aims at creating synergies between innovation (e.g., research), the market (SMEs), and the public sector (PPP).

So, what’s left? Well, society!

The third policy pillar is ensuring that AI works for people (which we will abbreviate as aiPeople). This pillar covers all the parts related to: (i) educating and training people on AI (including efforts to preventexperts from fleeing to the US), (ii) maintaining social cohesion, and (iii) making the EU a leader in AI regulation.

To fully understand what these efforts are about, we need to first “partire per la tangente” and introduce the EU digital Strategy|Decade|Programme|Compass (yes, these are all different things, and there are more12).

EU Digital Initiatives

Let’s start with the European Digital Strategy (EDS). The EDS is the overarching framework under which all other digital initiatives reside. It was first introduced in 2020 in this press release as a successor to the Digital Agenda and has BIIIG objectives. Among those, the one that I’m most excited for is the “single digital market”, which addresses the fragmentation problem we’ve discussed before.

In March 2021, the Commission proposed the Digital Decade (DigiDec) as a structured policy programme to implement the goals of the EDS. Essentially, the EDS had big plans, and the DigiDec laid out a way to achieve them. However, the DigiDec is still not specific enough; for example, it does not provide metrics to measure whether the goals have been achieved.

Enter the Digital Compass (DigiCompass). If you click on the link for the DigiCompass, you will notice that it is one of those long, detailed EU Commission document. This is where all the metrics and objectives from the DigiDec are defined. If you have time to spare, you can scroll all the way down to the annex, where you’ll find a table of “cardinal points”, aka objectives. Among those, we finally see goals related to AI, such as:

- Increasing the number of employed ICT specialists to at least 20 million, some of whom will focus on AI.

- Achieving 20% of global semiconductor production value in Europe, including those for AI factories.

- Ensuring that at least 75% of European enterprises have adopted AI.

Ok, all very cool, but where does the money come from? You guessed it, the last piece of the puzzle is the Digital Europe Programme (DigiProg). It has a budget of €7.9 billion and is responsible for financing EDIH, GenAI4EU, and AIoD.

Nurturing Talent and Improving Skills

This point is quite straightforward. The EU aims to develop AI literacy and expertise among its citizens. There are two levels at which they approach this, depending on the level of specialization desired:

- Basic Level: Covers AI literacy, i.e. knowing AI exists and how to use it. This is formulated as “teaching professionals in all sector about AI” (as part of the Skills Agenda), hoping they will use AI in their work13. It’s also nice to see a focus on integrating AI education in schools and supporting the use of AI to enhance teaching.

- Expert Level: Involves creating AI experts, aka PhDs. This is done both by funding the creation of new experts (e.g. Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions) and facilitating their mobility across EU (e.g., through the NoEs we saw before)

Developing a Policy Framework to Ensure Trust in AI Systems

Basically ensuring that AI doesn’t screw up society. It all started in 2018, when the High-level expert group on artificial intelligence (AI HLEG) wrote the guidelines of trustworthy AI (you can find them here). These guideline were then expanded upon in the White Paper on AI in 2020, and realistically served as the basis for parts of the EU AI ACT. Interestingly, these guidelines also cover measures to adapt liability frameworks for AI and to enhance cybersecurity defenses against attacks14, which are bound to become a bigger issue with AI).

Promoting the EU Vision on Sustainable and Trustworthy AI in the World

Unlike the other two pillars, this one looks beyond the EU and aims to establish the EU as a leader in human-centric AI policies. Following the principles found in the Digital Compass the EU launched the International outreach for human-centric artificial intelligence initiative. Its aim is to involve as many international partners as possible, including the UN, UNESCO, OECD, Council of Europe, G7, and G20, to work together on AI. Specifically the EU:

- Is a funding member of the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI), launched in July 2020.

- Collaborates with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) through the ONE-AI experts group and the AI watch

- “Support international standadization bodies in their work to define common standards in the global governance of AI”.

On the last point we need to open a small parenthesis. The EU is not doing this purely out of altruism. The country that manages to set a standard that is later accepted internationally often has an intrinsic advantage on the competitors. That is why in the Coordinate Plan for AI (Annex 1, Chapter 10) mentions both the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), which are engaged in a wide range of standardization activities.

4. Build Strategic Leadership in High-Impact Sectors

We finally reached the last point. This one focuses more on the sectors where AI can (and will) have a significant impact. Since it’s pretty straightforward, I’ll list them here and provide some context:

- Environment : You probably know about the Green Deal, where the EU aims to become climate neutral by 2050. Here, they mention that AI can help in several ways (e.g., energy/resource efficiency, finding solutions to climate change), but they also acknowledge its environmental footprint15, thus promoting research and development in green AI initiatives16.

- Health : It’s no surprise that the healthcare system needs to undergo serious changes to survive in the coming decades. In this light, the EU aims to digitize health data with the European Health Data Spaces to use AI to support the whole system.

- Robotics : You’ve probably seen the Figure 02 Robot and heard about all the promises regarding “automating service sectors”. That’s the whole point17.

- Public sector : This is something I’m super excited about! We are all painfully aware of the inefficiencies and excessive bureaucracy (looking at you, Deutschland) that plague our systems. The introduction of AI can streamline bureaucratic processes (I sound like ChatGPT now) and potentially enhance democratic system. The first studies on AI supporting democracy are already looking good (cough cough Multi Agent Systems).

- Home affairs : Unlike the previous point, this one makes me a bit uneasy. It discusses the use of AI in law enforcement. They do mention that the AI should never have the final say, but the whole narrative is primarily centered around terrorism. This has often been used as a justification to introduce laws and policies that restrict citizens’ privacy and liberty. Because, of course, no one wants terrorism.18.

- Transport : Since moving to Germany, I’ve noticed how the traffic lights work based on how many cars are waiting. I love it. While this is not the AI we often imagine for “smart mobility,” it does contribute to more efficient transport. The actual initiative for transport goes more in detail (covering aviation, rail, inland waterways and road transport sectors), basically revolving around the Mobility Strategy

- Agriculture : The EU has recognized that the “AI-enabled precision farming is estimated to grow and reach EUR 11.8 billion by 2025” and they want a piece of the cake.

To summarize, these initiatives are sector-specific and are also tied to the Testing and Experimentation Facilities we discussed earlier.

Conclusion

And we’re finally done. For you, this might have been a 20-minute read (according to the average reading speed) , but for me, it took three weeks of my “free time” (I really should find a new hobby).

Take-Aways: If You Didn’t Read, Here’s the Comprehensive List

If you’re in a rush, here are the key points from this post, along with the insights from digging into the EU AI policies:

- Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence (PlanAI):

- Initially published in 2018 and reviewed in 2021 to emphasize human-centric AI, sustainability, and achieving EU digital sovereignty.

- Significant funding increase, aiming for €145 billion by 2023 through various EU initiatives like Horizon Europe and Digital Europe Programme.

- AI Factories:

- Announced for 2025, AI Factories will combine supercomputers, data centers, and human expertise to boost AI development across industries, supported by €2.1 billion in investments.

- GenAI4EU:

- Focuses on industrial and public sector AI applications with €500 million in funding, closely tied to AI Factories and Common European Data Spaces for infrastructure support.

- Thriving From the Lab to the Market:

- Aiming to foster public-private partnerships (PPP) through €1 billion per year investments, with additional funding from member states and private sectors.

- AI-on-Demand (AIoD) Platform:

- A central marketplace for AI assets (datasets, models), research bundles, and services like AI builders and innovation labs.

- European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs):

- These regional hubs support digital transformation and AI adoption at the local level, with around 150 hubs currently in operation.

- Testing and Experimentation Facilities (TEFs):

- Sector-specific facilities for testing AI applications in real-life environments (e.g., healthcare, agriculture, smart cities), helping startups and SMEs bring their innovations to market.

- ADRA (AI, Data, and Robotics Association):

- A critical body managing the collaboration between academia, startups, and industry, driving European AI advancements while balancing societal and economic goals.

- Educational and Societal Focus:

- The EU aims to boost AI literacy for professionals and develop new AI experts through PhD programs, while ensuring AI applications align with EU values and benefit society as a whole.

- Global AI Leadership:

- The EU is positioning itself as a global leader in human-centric AI through collaborations with international organizations like the UN and OECD, while also setting standards for trustworthy AI development.

The PlanAI is vast and interconnected, with many moving parts. By understanding these frameworks, we get a clearer picture of how the EU intends to achieve digital sovereignty and ensure that AI works for both industry and society.

Personal Considerations

This deep dive has taught me a lot about the EU AI landscape (even though we only covered one plan from four years ago), and I hope it helps you understand just how complex this whole ecosystem is. In my previous post, I showed how the Horizon projects have overlaps and inefficiencies, particularly in AI-related initiatives. My aim here was to summarize how the EU is managing AI, potentially highlight some reasons behind these inefficiencies, and suggest solutions. While I still aim to do that, I was naive to think the answer could come from just a few weeks of research.

Interestingly, the word “fragmentation” appeared repeatedly in many of the documents I read while writing this blog post. The EU is painfully aware that fragmentation is one of its most significant issues, one that could slowly kill the Union if left unaddressed (as pointed out in Mario Draghi’s report). However, it’s clear that this is not an easy problem to solve.

That said, I’m still committed to finding a solution to the inefficiencies within Horizon projects, and I’ll continue investigating how the entire funding process works, particularly for AI initiatives. s. This research is also essential for working on the CAIRNE proposal for a CERN-like hub for AI, which aims to address these fragmentation issues more comprehensively. In future posts, you can expect more content along these lines, and I’ll also keep updating the AI initiatives graph.

Lastly, while I write these blog posts because I genuinely believe that teaching others is the best way to fully understand a topic, it does take time and effort. So, if you appreciated this post, please let me know by leaving a comment and engaging.

Footnotes

-

Euractive article. I can’t access the science business one :( ↩

-

The RRF allocated these €134 billions for project aiming to digitalize the EU. So, while these funds are not exclusively allocated to AI initiatives, AI initiatives are indeed included. ↩

-

Previously called CLAIRE. ↩

-

The term “innovative” here refers to ideas that likely originate from an academic context. ↩

-

The private sector part of the idea. This refers to guiding the private sector by offering expertise in both technical (previous point) and regulatory areas. ↩

-

Societal and environmental considerations will need to align with strict EU regulations and the AI Act, which aims to prevent the implementation of risky AI use cases. ↩

-

The goal for companies is profit, and AI has the potential to generate significant financial returns. ↩

-

As we discussed before, ADRA does much more, but stick with me for this example. ↩

-

If you wonder how the DMAT compares to the Technology Readiness Level (more about it later), basically the DMAT is about how ready an organization is to adopt digital transformation, whereas TRL focuses on how ready a particular technology is for implementation. ↩

-

Fun fact, ELISE it used to be called European Learning and Intelligent Systems Excellence (according to the proposal). ↩

-

I challenged myself to find as many EU initiatives starting with “digital” as possible. Here is a (still incomplete) list: (1) Digital Economy and Society Index, (2) Digital Services Act, (3) Digital Markets Act, (4) Digital Agenda for Europe,(5) Digital Action Day, (6) Digital Euro, (7) Digital Education Action Plan, (8) Digital Opportunity Traineeships ↩

-

Part of the work done in the Digital Education Action Plan (Action 8) was to update the Digital Competence Framework to its 2.2 version to include AI. ↩

-

In the EU Cybersecurity Strategy for the Digital Decade it’s written “Cybersecurity must be integrated into all these digital investments, particularly key technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI), encryption and quantum computing […]” ↩

-

Short rant on what the former CEO of Google said a few days ago, namely “that pursuit of AI should take precedence over climate change”. While I do understand his point that AI can drive innovation and ultimately address climate issues, what happens if AI does NOT fideliver a solution in time? Are we seriously betting the future of our planet on this hope? Bah. ↩

-

The complete proposal (Chapter 11 here) suggests a number of cool initiative, along with R&D efforts. These include the creation of green data spaces and AI-supported digital simulation of the planet through the Destination Earth initiative. ↩

-

One aspect that was depressing to read is how the document mentions demographic challenges as a reason for needing automation. Sure, automation could help, but you know what else could address this issue? Immigration. It feels like we’re prioritizing robots over people, instead of leveraging human potential. I’d rather see people of diverse backgrounds on the streets than robots. ↩

-

After the 9/11 terrorist attack, the U.S. introduced the USA PATRIOT Act (lol the name), which expanded surveillance power of law enforcement. This later led to controversies like the NSA surveillance exposed by Edward Snowden, showing that these powers were used to monitor U.S. citizens). ↩